Book Projects

|

Over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, several of the artists who would come to be known as the greatest of all modernist painters made artworks with a similar essential content. From paintings showing women being gruesomely murdered by Eugene Delacroix to the erotically charged depictions that Paul Gauguin made of his thirteen-year-old Polynesian bride—much of what is now considered the most important modern art focused repeatedly on either violent, degrading, or demeaning depictions of women.

THE MISOGYNISTS: A History of Modern Art in Six Painters is the first book to urgently investigate the behavior of not only these artists, but also that of their most renowned contemporaries—Gustave Courbet, Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir, and Pablo Picasso—to uncover the ways that artworks reflected negative attitudes towards women which have become a vital underlying element in art history. The book methodically situates the work of these men within each of their respective historical eras to reveal the ways that each not only shocked their contemporaries but exceeded even the harshest of dominant dialogues surrounding gender roles in the period. |

Russian Orientalism in a Global Context brings together eleven essays by an international group of scholars to investigate the ways that Russian visual culture was impacted by encounters—both real and imagined—with the representational traditions of the so-called East or Vostok.

Following the Napoleonic wars, the Russian Empire’s aggressive expansionist campaigns led to the annexation of vast new lands in the Caucasus and Central Asia, resulting in the large-scale assimilation of religiously and ethnically diverse groups of people. However, given the country’s perpetually conflicted self-identification as neither fully European nor quintessentially Asian, the established Western European genre of Orientalist painting remained ambiguous and elusive in the Russian context, challenging the fixed Saidian binary that has dominated postcolonial discourse. For Russian artists the demarcations between the “self” and the “other” were much more porous than for their French and British counterparts, resulting in an Orientalist mode that was more prone to hybridity, syncretism, and even self-Orientalization. |

Articles and Anthology Chapters

“Masculinity and Partnership: The Artel of Artists, the Peredvizhniki, and Fraternal Values from 1863-1885”

To be published in Russian under the title:

“Мужское начало и товарищество: артель художников, передвижники и братские ценности 1863–1885”

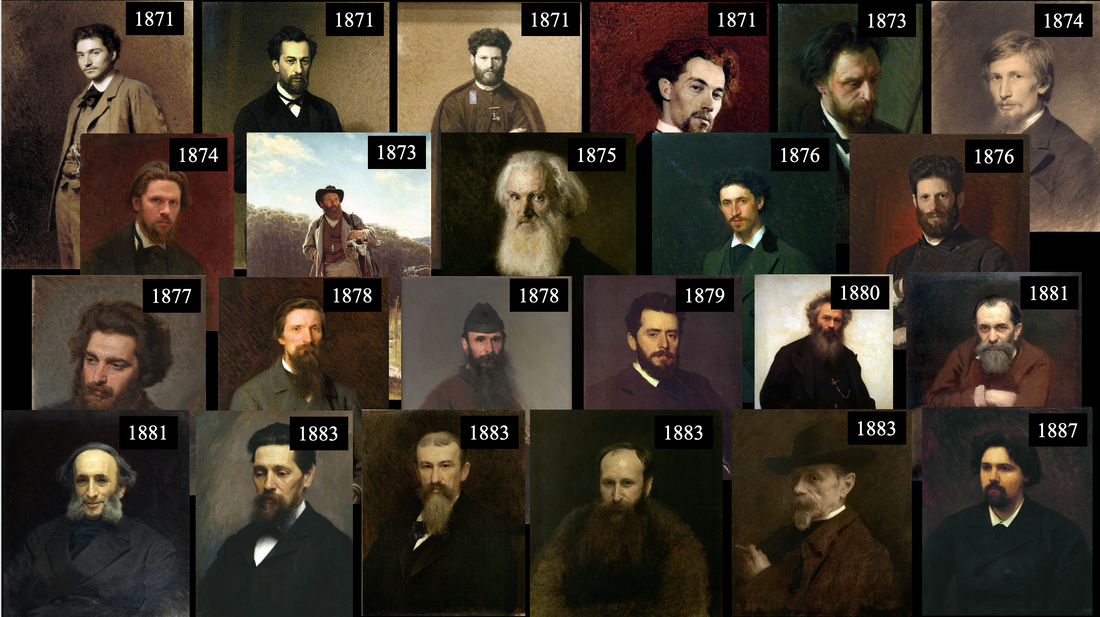

Recent scholarship has reassessed the factors that led to the formation of the Peredvizhniki group as well as its overarching values and ideological underpinnings. In many ways, the Peredvizhniki can be seen as a remarkable experiment in artistic collectivism, but what has so far not been thoroughly evaluated is the unique sense of fraternal values and masculine solidarity which characterized the group from its inception. Building off the recent work of Andrey Shabanov, this talk explores the notion of tovarishchestvo or “partnership” in the work of Ivan Kramskoi and examines how he cultivated conceptions of brotherhood and masculine solidarity by creating numerous portraits of his fellow artists. By returning the group to its original social and exhibitionary context, it becomes clear that the partnership reflected larger values surrounding the importance of male bonds in the second half of the century.

To be published in Russian under the title:

“Мужское начало и товарищество: артель художников, передвижники и братские ценности 1863–1885”

Recent scholarship has reassessed the factors that led to the formation of the Peredvizhniki group as well as its overarching values and ideological underpinnings. In many ways, the Peredvizhniki can be seen as a remarkable experiment in artistic collectivism, but what has so far not been thoroughly evaluated is the unique sense of fraternal values and masculine solidarity which characterized the group from its inception. Building off the recent work of Andrey Shabanov, this talk explores the notion of tovarishchestvo or “partnership” in the work of Ivan Kramskoi and examines how he cultivated conceptions of brotherhood and masculine solidarity by creating numerous portraits of his fellow artists. By returning the group to its original social and exhibitionary context, it becomes clear that the partnership reflected larger values surrounding the importance of male bonds in the second half of the century.

Top Image:

Portraits of Artists made by Ivan Kramskoi between 1871 and 1887 (photograph by the author).

[Top row: Портрет Ф.А. Васильева. 1871; Портрет М.К. Клодт. 1871, oil on canvas. 89 × 69, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет М. Антокольского. 1871, oil on canvas. 88 × 67, State Museum of Belarus, Minsk; Портрет К.А. Савицкого. 1871, oil on cardboard, Voronezh Regional Art Museum. Inv. Ж-319; Портрет Г.Г. Мясоедова. 1872, oil on canvas, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет И.И. Шишкин. 1873, oil on canvas. 110.5 × 78, State Tretyakov Gallery]

[Second row: Автопортрет. 1874, oil on cardboard. 42.5 × 34, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет В.М. Васнецова. 1874, sauce, pencil, and ceruse on paper. 60 × 44.6, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет М.Б. Дьяконова. 1875, oil on canvas. 75.6 × 62.2, State Russian Museum; Портрет И.Е. Репина. 1876; Портрет М.М. Антокольского. 1876, oil on canvas. 75 × 63.5, State Russian Museum. Inv. Ж-2990]

[Third row: Портрет А.И. Куинджи. 1877, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет К.Ф. Гуна. 1878, oil on canvas. 85.5 × 70, Scientific-Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts; Портрет А.Д. Литивченко. 1878, oil on canvas. 96 × 69, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет П.А. Брюллова. 1879, oil on canvas, State Russian Museum; Портрет И.И. Шишкин. 1880, oil on canvas. 115.5 × 83.5, State Russian Museum; Портрет В.Г. Перова. 1881, oil on canvas. 81 × 71, State Russian Museum. Inv. Ж-2985]

[Bottom row: Портрет И.К. Айвазовский. 1881, oil on canvas. 67 × 64, Феодосийская картинная галерея имени И. К. Айвазовского; Портрет А. А. Киселева. 1883, oil on canvas. 44.6 × 34.6, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет А. П. Соколова. 1883; Портрет В.В. Верещагина. 1883, oil on canvas. 78.2 × 68.7, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет А.Г. Деньера. 1883, oil on canvas. 65 × 55.5, State Russian Museum; Портрет В.И. Сурикова. 1887, oil on canvas. 73.5 × 59.5; Красноярский художественный музей В.И. Сурикова (all paintings by Ivan Kramksoi)]

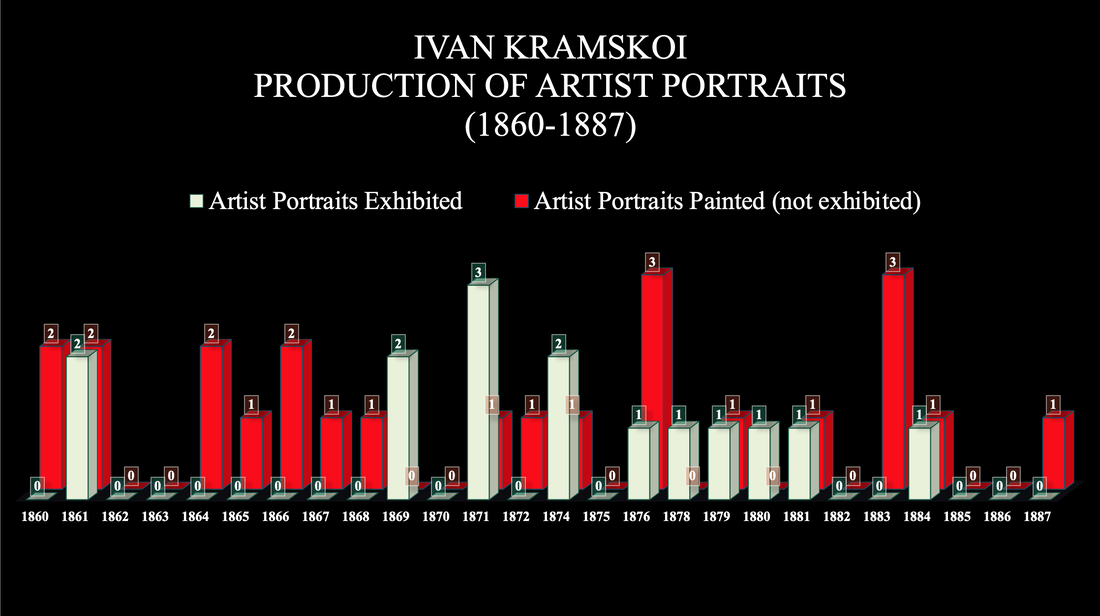

Bottom Image:

2-Axis column bar graph showing I.N. Kramkoi’s production of artist portraits between 1860 and 1887 (photograph by the author).

Portraits of Artists made by Ivan Kramskoi between 1871 and 1887 (photograph by the author).

[Top row: Портрет Ф.А. Васильева. 1871; Портрет М.К. Клодт. 1871, oil on canvas. 89 × 69, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет М. Антокольского. 1871, oil on canvas. 88 × 67, State Museum of Belarus, Minsk; Портрет К.А. Савицкого. 1871, oil on cardboard, Voronezh Regional Art Museum. Inv. Ж-319; Портрет Г.Г. Мясоедова. 1872, oil on canvas, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет И.И. Шишкин. 1873, oil on canvas. 110.5 × 78, State Tretyakov Gallery]

[Second row: Автопортрет. 1874, oil on cardboard. 42.5 × 34, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет В.М. Васнецова. 1874, sauce, pencil, and ceruse on paper. 60 × 44.6, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет М.Б. Дьяконова. 1875, oil on canvas. 75.6 × 62.2, State Russian Museum; Портрет И.Е. Репина. 1876; Портрет М.М. Антокольского. 1876, oil on canvas. 75 × 63.5, State Russian Museum. Inv. Ж-2990]

[Third row: Портрет А.И. Куинджи. 1877, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет К.Ф. Гуна. 1878, oil on canvas. 85.5 × 70, Scientific-Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts; Портрет А.Д. Литивченко. 1878, oil on canvas. 96 × 69, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет П.А. Брюллова. 1879, oil on canvas, State Russian Museum; Портрет И.И. Шишкин. 1880, oil on canvas. 115.5 × 83.5, State Russian Museum; Портрет В.Г. Перова. 1881, oil on canvas. 81 × 71, State Russian Museum. Inv. Ж-2985]

[Bottom row: Портрет И.К. Айвазовский. 1881, oil on canvas. 67 × 64, Феодосийская картинная галерея имени И. К. Айвазовского; Портрет А. А. Киселева. 1883, oil on canvas. 44.6 × 34.6, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет А. П. Соколова. 1883; Портрет В.В. Верещагина. 1883, oil on canvas. 78.2 × 68.7, State Tretyakov Gallery; Портрет А.Г. Деньера. 1883, oil on canvas. 65 × 55.5, State Russian Museum; Портрет В.И. Сурикова. 1887, oil on canvas. 73.5 × 59.5; Красноярский художественный музей В.И. Сурикова (all paintings by Ivan Kramksoi)]

Bottom Image:

2-Axis column bar graph showing I.N. Kramkoi’s production of artist portraits between 1860 and 1887 (photograph by the author).